Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common challenges a trainer will encounter when working with older clients. OA is the leading cause of disability in the older population primarily because it limits physical activity so much. People with OA tend to limit their activities because they are painful. The lack of physical activity causes an acceleration of the loss of muscle mass association with aging so individuals becoming weaker faster. This leads to even further self-limitations in physical activity which accelerates the process even more. It is a vicious downward cycle we so commonly witness.

Often older adults with OA need to regularly perform some type of resistance training because they are typically weaker than people their age without OA. However, they are less likely to perform resistance training because it is uncomfortable and irritating to their joints. Many also feel that it will damage their joints further and accelerate the arthritic process. This couldn't be further from the truth. Resistance training is an essential component in an exercise program for those with OA because it has been shown to decrease arthritic symptoms, improve strength and improve function. It is generally recommended that individuals use lower loads and higher repetitions which fits in well with a functional exercise approach that emphasizes movement patterns rather than brute strength. Keeping the loads lighter will definitely help reduce the joint pain and irritation that accompany resistance training but range of motion is also an important factor to consider.

I have found that some individuals with knee OA are more sensitive to range of motion compared to loading. For these clients, lower-body movements such as squats, lunges and step-ups can be performed effectively if depth is limited. Many trainers have difficulty telling a client that it is okay to not go to horizontal on a squat because they have been taught that a good squat requires depth. However, a shallow squat that can be performed well and without discomfort is better than a deeper squat that is painful for days to come. Performing a movement with idealâ form is not the goal with these clients (although it is great if they can). Instead focus on being successful within their personal limits of range of motion and loading.

If you want to be successful with these clients then you need to be ready to tweak their program based on the feedback you are getting from them. Try to discern which movements are causing them the most irritation and either change one of the movement parameters (depth, distance, load, speed, height, direction, etc.) or swap out the movement for one that is similar. It can be difficult to determine which movement (or movements) is causing them the most problems so trainers need to be systematic in their approach to the exercise program. Only introduce one or two new movements (or tweaks) at a time so that you can gauge their reaction to the change over the course of several sessions. However, it is often not the exercise program that is the issue but, instead, what they are doing outside of their exercise program. So don't be too quick to throw out exercises. A client may come in to train on Monday after having spent the past two days shopping or doing yard work so their joints are already irritated.

You should expect acute exercise to be somewhat uncomfortable for the arthritic client but over time, if they are consistent with their program, they should be able to tolerate exercise better. Encourage your clients to manage their arthritic symptoms holistically proper nutrition and hydration, weight loss, avoid high-impact activities, and use NSAIDs (or other anti-inflammatories as directed by their physician). Glucosamine and chondroitin supplements have been shown to improve cartilage deterioration and arthritic symptoms in some people. Before their exercise session they should perform an extended gradual warm-up to help lubricateâ the joints. It is also helpful to take a hot shower or soak in the hot tub beforehand.

In my experience I have found that the seated knee-extension exercise is problematic for most adults with knee OA. In fact, I typically do not include it at all in an exercise routine if clients state they have knee OA. Instead, we work on closed-chain functional movement patterns that utilize the quadriceps muscles in combination with the hamstrings, glutes, calves, etc. These are typically well-tolerated especially if we are aware of their personal limitations on loading and range of motion.

High-impact exercises in which both feet are off of the ground at the same time should also generally be avoided. This includes jumping rope, running, skiing and other similar activities. Modifying these high-impact movements to make them low-impact is appropriate (whenever possible). For example, a typical burpee requires people to jump off the ground; instead you can have them simply stand up and reach their arms above their head.

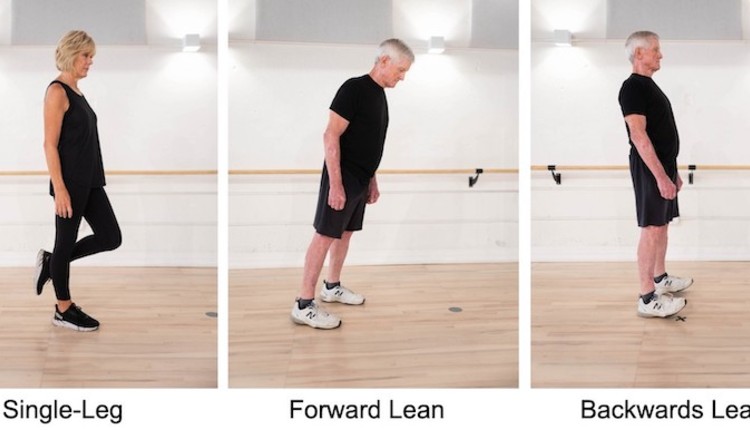

In most cases an extended warm-up will help clients tolerate the exercise program better. They will be able to perform more resistance exercises with less pain. Warm-up should include some general cardiovascular movement as well as joint-specific movements especially for the affected joints. About 10 minutes of low- or no-impact cardio modes such as a recumbent cycle, Nustep (recumbent stepper), elliptical or treadmill at a low to moderate intensity should be sufficient. Mini-lunges and mini-squats with bodyweight only are also helpful for the hips, ankle and knees. For the upper extremities performing arm swings, overhead reaches, shoulder shrugs and shoulder rolls are useful. In addition, try to mimic the same movements that they are going to perform during their exercise routine. If you have side lunges planned then the warm-up could include side steps with mini-squats and lateral weight shifting with a reach while in a wide-stance position.

Just like the warm-up, cardiovascular routines for arthritic clients should be performed on low or no-impact modes. However, in other aspects (time, intensity and frequency) the routines really don't differ significantly from those of non-arthritic clients. I have found that reducing range of motion also helps clients perform their cardio routine with less pain and aggravation. For example, on the elliptical machine I typically lower the ramp (level 3-5/10) and on the Nustep I move the seat back a little so that the steps are smaller. These tweaks tend to help people tolerate the exercises better.

Arthritis in the spine can be very debilitating and painful. To warm-up the back and trunk, have the client perform unloaded flexion/extension, lateral flexion and rotation within a small range of motion and in a very controlled manner. The motion should be gentle and rhythmic. Avoid having the client try to go as far as they can in any direction.

It is vital that you limit spinal motion during the exercise program. Therefore, avoid traditional abdominal exercises such as crunches, sit-ups, side bends and medicine ball rotations. Instead, teach the client how to maintain a neutral spine and focus on multi-planar (sagittal, frontal, transverse) spinal stability and build isometric endurance. Exercise movements such as bird dogs, front planks, side planks, standing cable rows, standing chest presses and dumbbell deadlifts are examples of isometric trunk movements that build core endurance. These types of exercises have been shown to minimize compressive loading of the spine compared to traditional abdominal exercises.

The bottom line is that it is important to understand your client's conditions, needs and capabilities. Arthritis affects people in many different ways and to varying degrees. Therefore, spend time with your client to learn how they will respond to exercise movements and training methods. A one-size-fits-all approach isn't appropriate and will lead to poor outcomes for both the client and trainer.

Often older adults with OA need to regularly perform some type of resistance training because they are typically weaker than people their age without OA. However, they are less likely to perform resistance training because it is uncomfortable and irritating to their joints. Many also feel that it will damage their joints further and accelerate the arthritic process. This couldn't be further from the truth. Resistance training is an essential component in an exercise program for those with OA because it has been shown to decrease arthritic symptoms, improve strength and improve function. It is generally recommended that individuals use lower loads and higher repetitions which fits in well with a functional exercise approach that emphasizes movement patterns rather than brute strength. Keeping the loads lighter will definitely help reduce the joint pain and irritation that accompany resistance training but range of motion is also an important factor to consider.

I have found that some individuals with knee OA are more sensitive to range of motion compared to loading. For these clients, lower-body movements such as squats, lunges and step-ups can be performed effectively if depth is limited. Many trainers have difficulty telling a client that it is okay to not go to horizontal on a squat because they have been taught that a good squat requires depth. However, a shallow squat that can be performed well and without discomfort is better than a deeper squat that is painful for days to come. Performing a movement with idealâ form is not the goal with these clients (although it is great if they can). Instead focus on being successful within their personal limits of range of motion and loading.

If you want to be successful with these clients then you need to be ready to tweak their program based on the feedback you are getting from them. Try to discern which movements are causing them the most irritation and either change one of the movement parameters (depth, distance, load, speed, height, direction, etc.) or swap out the movement for one that is similar. It can be difficult to determine which movement (or movements) is causing them the most problems so trainers need to be systematic in their approach to the exercise program. Only introduce one or two new movements (or tweaks) at a time so that you can gauge their reaction to the change over the course of several sessions. However, it is often not the exercise program that is the issue but, instead, what they are doing outside of their exercise program. So don't be too quick to throw out exercises. A client may come in to train on Monday after having spent the past two days shopping or doing yard work so their joints are already irritated.

You should expect acute exercise to be somewhat uncomfortable for the arthritic client but over time, if they are consistent with their program, they should be able to tolerate exercise better. Encourage your clients to manage their arthritic symptoms holistically proper nutrition and hydration, weight loss, avoid high-impact activities, and use NSAIDs (or other anti-inflammatories as directed by their physician). Glucosamine and chondroitin supplements have been shown to improve cartilage deterioration and arthritic symptoms in some people. Before their exercise session they should perform an extended gradual warm-up to help lubricateâ the joints. It is also helpful to take a hot shower or soak in the hot tub beforehand.

In my experience I have found that the seated knee-extension exercise is problematic for most adults with knee OA. In fact, I typically do not include it at all in an exercise routine if clients state they have knee OA. Instead, we work on closed-chain functional movement patterns that utilize the quadriceps muscles in combination with the hamstrings, glutes, calves, etc. These are typically well-tolerated especially if we are aware of their personal limitations on loading and range of motion.

High-impact exercises in which both feet are off of the ground at the same time should also generally be avoided. This includes jumping rope, running, skiing and other similar activities. Modifying these high-impact movements to make them low-impact is appropriate (whenever possible). For example, a typical burpee requires people to jump off the ground; instead you can have them simply stand up and reach their arms above their head.

In most cases an extended warm-up will help clients tolerate the exercise program better. They will be able to perform more resistance exercises with less pain. Warm-up should include some general cardiovascular movement as well as joint-specific movements especially for the affected joints. About 10 minutes of low- or no-impact cardio modes such as a recumbent cycle, Nustep (recumbent stepper), elliptical or treadmill at a low to moderate intensity should be sufficient. Mini-lunges and mini-squats with bodyweight only are also helpful for the hips, ankle and knees. For the upper extremities performing arm swings, overhead reaches, shoulder shrugs and shoulder rolls are useful. In addition, try to mimic the same movements that they are going to perform during their exercise routine. If you have side lunges planned then the warm-up could include side steps with mini-squats and lateral weight shifting with a reach while in a wide-stance position.

Just like the warm-up, cardiovascular routines for arthritic clients should be performed on low or no-impact modes. However, in other aspects (time, intensity and frequency) the routines really don't differ significantly from those of non-arthritic clients. I have found that reducing range of motion also helps clients perform their cardio routine with less pain and aggravation. For example, on the elliptical machine I typically lower the ramp (level 3-5/10) and on the Nustep I move the seat back a little so that the steps are smaller. These tweaks tend to help people tolerate the exercises better.

Arthritis in the spine can be very debilitating and painful. To warm-up the back and trunk, have the client perform unloaded flexion/extension, lateral flexion and rotation within a small range of motion and in a very controlled manner. The motion should be gentle and rhythmic. Avoid having the client try to go as far as they can in any direction.

It is vital that you limit spinal motion during the exercise program. Therefore, avoid traditional abdominal exercises such as crunches, sit-ups, side bends and medicine ball rotations. Instead, teach the client how to maintain a neutral spine and focus on multi-planar (sagittal, frontal, transverse) spinal stability and build isometric endurance. Exercise movements such as bird dogs, front planks, side planks, standing cable rows, standing chest presses and dumbbell deadlifts are examples of isometric trunk movements that build core endurance. These types of exercises have been shown to minimize compressive loading of the spine compared to traditional abdominal exercises.

The bottom line is that it is important to understand your client's conditions, needs and capabilities. Arthritis affects people in many different ways and to varying degrees. Therefore, spend time with your client to learn how they will respond to exercise movements and training methods. A one-size-fits-all approach isn't appropriate and will lead to poor outcomes for both the client and trainer.