How many of your clients have chronic nagging pain or recent injuries? Early in my career as both a physical therapist and fitness professional, I made the mistake of thinking a program made of therapy exercises and gym-based workarounds would improve client function.

While some clients made progress, many spiraled deeper into the chronic injury cycle. What I didn’t understand is why my program design was ultimately ineffective at bridging the gap from rehab to fitness and performance. Let’s uncover why this method doesn’t work, and what nuances fitness professionals can incorporate to bridge the gap for high-level fitness restoration.

Why rehab exercises don’t bridge the gap

When rehab professionals select exercises, they are targeted toward specific deficits that the licensed provider identified by performing tests like joint play, goniometry, manual muscle testing and neurokinetic testing. The therapist also considers the stage of tissue healing and other medical factors to dose exercise interventions. Such selective exercise prescription to solve a movement or tissue healing problem is like taking cough medicine to calm a cough. Once the cough has calmed, taking medicine for additional days or increasing the dose is not beneficial.

When repeating the rehab for fitness program design, one of two outcomes emerges:

1. Injured tissue over-dosing, which leads to inflammation, pain and decreased function.

2. Wasting valuable client time by repeating exercises aimed at a plateau.

Why it doesn’t work to progress injury work-around programs

A common question fitness professionals ask rehabilitation providers is “what should my client avoid?” The answer helps create work-around exercises in the fitness environment. Work-around workouts, however, are not designed for long-term use.

Creating long-term work-arounds leads to stress shielding. This means that the weak structures are protected, or shielded, from working while stronger muscles subtly compensate. This strategy increases the muscle performance discrepancy between weaker regions and stronger regions. Creating progressions that increase the gap leads to a chronic cycle of decreasing functional movement options, and increasing compensation. When the fitness enthusiast or athlete is cleared by the medical team for return to full participation, the body’s regional discrepancies facilitate a cascade of emerging injuries.

A better strategy to bridge the performance gap

If rehab exercise and work-around workouts don’t fill the return to performance gap, what strategies help? The answer lies in unveiling the nuances of post-rehab program design. Let’s explore the post-rehab formula in three phases: 1) Restoring tissue tolerance, 2) Expanding functional movement capabilities and 3) Coaching techniques.

Step 1: Program design to restore tissue tolerance

Ever see clients sidelined by injury in the first 30 days of their post-rehab return to fitness? When clients return to the fitness post-injury, they are tempted to jump in where they left off. This rushed approach leads to disappointing injury-sidelining outcomes. A common misconception sounds like “If you can stand from the chair, then you can do squats.” This misconception is rooted in a lack of understanding realistic tissue healing times, and how to develop tissue tolerance for repetition, load and speed while minimizing risk.

Even though clients may feel that muscles are ready to go, other tissues like ligaments, tendons, fascia and bone work, too. While musculotendinous injuries can often withstand previous loads and speeds within 6 months of injury, ligaments and bones often take 1-2 years to remodel. It is not uncommon to see a frustrated athlete 4 months after ACL repair attempting return to fitness. The graft is weakest at this point, even though the athlete feels ready to work out. Fitness professionals must initiate communication with the medical team to understand safe boundaries and timeframes instead of relying solely on client motivation.

After establishing boundaries, fitness professionals can help restore muscle performance capabilities such as endurance, strength and power. Restoring tissue tolerance and performance requires attention to post-rehab nuances in exercise selection, order and acute variable (load, sets, reps and rest) progression.

Exercise selection — Initially, progressively loaded isolated exercises (i.e. most machine-based exercises) present a helpful solution. Early compound or loaded functional exercises (i.e. squats, lunges, pushups) may lead to stress shielding. Such compensation would widen, as opposed to bridging the post-rehabilitation to performance gap. When selecting exercises, a key question fitness professionals should ask rehabilitation providers is, “Can the client do both open and closed chain exercises?” The answer offers guidance in safe exercise selection.

Order of exercises — As neuromuscular control fatigues throughout a session, more performance errors emerge, which increases injury risk. Fitness professionals need to both include proper exercise order to minimize pre-mature fatigue and be attentive to non-verbal signs. Follow this formula to help minimize risk: 5-10 minute general multi-planar warm-up Isolated activation exercises or brief stretches for targeted areas Workout-specific warm-up sets Working sets beginning with the most neurologically and energetically demanding 5-10-minute cool-down The cool-down is often the most overlooked injury prevention window. Cool-down includes not only activities that restore baseline physiology, but also a discussion of client-specific recovery, nutrition and hydration.

Load — Load should be different for activation, warm-up and working sets. Activation sets are designed to neurologically prime muscle participation. They typically target previously injured areas. Generally, there is no to minimal external load as the client performs one set of 10-15 reps. Common examples include glute bridges or light band shoulder rotation. Adding load or using compound functional movements will by-pass the key activation goal.

After activation, the warm-up set load is approximately 50% of the working load. It is designed to further prepare the neuromuscular connections and body tissues to withstand the subsequent working loads.

Working loads create metabolic, local hypertrophy, strength or power gains. While load for working sets is often stated as a percentage of 1RM, testing recovering tissues represents a safety concern. Instead, fitness professionals can select load by targeting a rep range for the desired training phase. If the load is too heavy, fitness professionals can guide the client to perform drop sets by decreasing the load within a set or between sets. Post-rehab should emphasize quality over quantity.

Repetitions — Repetitions influence whether the body responds with metabolic, muscular or neuromuscular performance gains, and restoration of efficient energy system use. Clients who have not engaged in a supplemental conditioning program during their rehabilitation will exhibit decreased metabolic efficiency.

When resistance training the number of repetitions achieved within each set influences set duration. Duration influences which energy system is predominantly developed. Retraining all the energy systems, beginning with aerobic and progressing to anaerobic (glycolytic and ATP-PC) will help restore essential performance capabilities.

Sets — Sets are governed by the amount of time a client has available for a session. Limiting activation and warm up to one set each helps decrease unnecessary fatigue. Increasing working sets facilitates hypertrophy and maximal strength as training progresses over several weeks.

Between set rest — While client motivation to restore performance and burn as many calories as possible quickly may lead to skipping or shortening rest periods, this decision bears unwanted cost relative to restoring tissue tolerance and performance. Maximizing performance requires increasing rest periods as load increases. Recommended rest periods respect the body’s physiology by aligning with ATP and central nervous system recovery needed to preserve quality over quantity. Initially, post-rehab clients will need the longer recovery times in each recovery range since their metabolic efficiency is a work-in-progress.

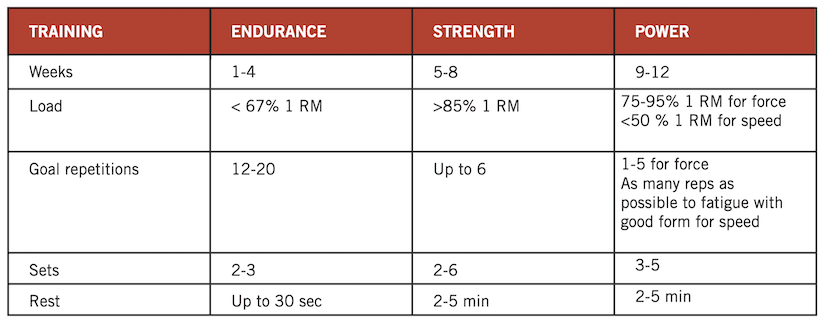

Progression — Restoring tissue tolerance and performance requires progression. Without progression, the client will reach a plateau before achieving his/her goals. The following chart summarizes common acute variable progressions through the muscle performance phases of endurance, strength and power.

While the body typically takes 4-6 weeks to adapt to a phase, the reality is acute variables operate on a continuum, as opposed to being discreet categories. Even within this reality, block or linear periodization, as opposed to undulating periodization, early in the return to training phase offers a better safety profile.

Next steps

Progressively re-establishing tissue tolerance is the first step to bridge the performance gap. The next step is learning how to expand the client’s movement options safely. This is followed by a third step: coaching strategies to influence how quickly performance capabilities emerge. Ready for the next steps? Stay tuned for the next two articles in this “Bridging the gap” series to learn the details.

Dr. Meredith Butulis, DPT, OCS, CEP, CSCS, CPT, PES, CES, BCS, Pilates-certified, Yoga-certified, has been working in the fitness and rehabilitation fields since 1998. She is the creator of the Fitness Comeback Coaching Certification, author of the Mobility | Stability Equation series, Host of the “Fitness Comeback Coaching Podcast,” and Assistant Professor the State College of Florida. She shares her background to help us reflect on our professional fitness practices from new perspectives that can help us all grow together in the industry. Instagram: @Dr.MeredithButulis.